The Soul’s Melody: A Journey into the Enchanting World of Urdu Shayari

In a world often dominated by haste and noise, there exists a sanctuary of words, a place where emotions are not just stated but painted with the finest brush of language. This sanctuary is the timeless and enchanting realm of Urdu shayari. More than mere poetry, Urdu shayari is the artistic expression of the soul, a delicate fusion of profound thought, musical language, and raw emotion that has captivated hearts for centuries. It is a universe where love and loss, joy and despair, philosophy and rebellion find their most eloquent voice. This intricate art form, born from a rich cultural synthesis, transcends geographical and linguistic boundaries to speak directly to the human condition. To engage with Urdu shayari is to embark on a journey into the deepest corridors of feeling, to experience the universal truths of life through a lens of unparalleled beauty and sophistication. Every couplet of Urdu shayari is a compact world, offering a mirror to our own experiences and a window into the sublime.

The very word ‘shayari’ stems from the Arabic ‘shi’r’, meaning poetry, but Urdu shayari evolved into something uniquely its own on the Indian subcontinent. It is not just a literary form but a living, breathing cultural phenomenon. It is recited in grand mushairas (poetic symposia), sung in soul-stirring melodies, whispered between lovers, and used as a source of solace and strength. The magic of Urdu shayari lies in its ability to convey the most complex emotions with stunning simplicity and layered meaning. A single couplet, or sher, can tell a complete story, pose a philosophical question, or capture a moment of intense passion. The language itself, Urdu, with its inherent grace and softness, lends a musicality to the verse that is almost hypnotic. This introduction is but a prelude to a deeper exploration of this magnificent art form, an invitation to understand why Urdu shayari continues to be a vital and cherished part of global cultural heritage.

The Historical Tapestry: Origins and Evolution of Urdu Shayari

The story of Urdu shayari is inextricably woven into the historical and cultural fabric of the Indian subcontinent. Its origins can be traced back to the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughal Empire, where Persian was the language of the court and culture. The early form of Urdu, then known as Hindavi or Dehlavi, began to absorb Persian linguistic and poetic influences, creating a new vernacular for poetic expression. The earliest pioneers of Urdu shayari, like Amir Khusrau (1253-1325), are legendary figures who brilliantly blended the indigenous sensibilities of Braj Bhasha with Persian imagery and forms. Khusrau, a disciple of the Sufi saint Nizamuddin Auliya, is often credited with laying the foundational stones for Urdu shayari, infusing it with mystical themes and a vibrant local flavor.

The evolution of Urdu shayari continued through the centuries, finding distinct voices in different courts. The Delhi school of thought, with poets like Mirza Muhammad Rafi Sauda and Khwaja Mir Dard, emphasized complexity and intellectual depth. However, a significant shift occurred as the Mughal capital moved to Lucknow in the 18th century. The Lucknow school, under the patronage of the Nawabs of Awadh, developed a style that was more ornate, focused on romance (ishq), elegance (nazakat), and sophistication (tehzeeb). This period saw the rise of poets like Mir Taqi Mir, who is often called the khuda-e-sukhan (god of poetry) for his unparalleled contribution to refining the language and emotion of Urdu shayari. His work, along with others, established the Ghazal as the premier form for expressing themes of unrequited love and spiritual longing.

The 19th and 20th centuries marked a golden age for Urdu shayari, a period of immense social and political change that was powerfully reflected in its verse. The trauma of the 1857 rebellion, the rise of Indian nationalism, and the eventual partition of India provided a fertile, albeit painful, ground for poetic innovation. This was the era of Mirza Ghalib, whose profound and often paradoxical couplets explored philosophy, love, and the absurdities of life with wit and deep sorrow. Later, the great Sir Muhammad Iqbal used Urdu shayari as a powerful tool to awaken the Muslim community, blending Islamic mysticism with a call for self-realization and action. The Progressive Writers’ Movement further revolutionized Urdu shayari, steering it towards themes of social justice, equality, and anti-imperialism through the powerful voices of Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Ali Sardar Jafri, and others. Thus, the history of Urdu shayari is a mirror to the history of its people, constantly evolving while retaining its core essence.

The Pillars of Expression: Major Forms and Structures in Urdu Shayari

To truly appreciate Urdu shayari, one must understand its primary structural forms, each with its own rules, aesthetics, and purpose. The two most significant pillars are the Ghazal and the Nazm, around which the entire edifice of Urdu shayari is built. The Ghazal is perhaps the most iconic and popular form, a collection of shers (couplets) where each sher is a self-contained pearl of thought, yet together they create a beautiful necklace on a common theme, usually love or loss. A traditional Ghazal follows a strict structure: both lines of the first sher (called the matla) rhyme, and the second line of every subsequent sher follows the same rhyme scheme (radif) and meter (beher). The final sher, called the maqta, often contains the poet’s pen name (takhallus).

In stark contrast to the fragmented beauty of the Ghazal stands the Nazm. A Nazm is a cohesive poem with a single theme or narrative that runs from beginning to end. It is characterized by its unity of subject, purpose, and development, much like Western poetry. The Nazm allows poets to explore complex stories, social commentaries, and philosophical ideas in a continuous flow, free from the rhyming constraints of the Ghazal. This form became the vehicle of choice for the Progressive Writers, who needed a broader canvas to paint their visions of social change. Other important forms in Urdu shayari include the Qasida (a panegyric or ode, often in praise of a patron), the Marsiya (a lamentation poem, specifically commemorating the martyrdom of Imam Hussain at Karbala), the Masnavi (a long narrative poem in rhyming couplets, used for epic tales and romances), and the Rubai (a quatrain with a specific rhyme scheme, perfect for delivering a concise philosophical punch).

Beyond these forms, the essence of Urdu shayari is captured in the standalone sher. A masterful sher is a universe in two lines. The first line (misra-e-oola) sets the scene, and the second line (misra-e-sani) completes it, often with a surprising twist, a profound insight, or a moment of breathtaking beauty. This structure demands immense precision and skill from the poet, to convey a world of meaning in just a few carefully chosen words. Understanding these forms is key to deconstructing the artistry behind Urdu shayari. It allows a reader to appreciate not just what is being said, but how it is being said—the intricate play of meter, rhyme, and structure that elevates words into art.

The Architects of Emotion: Legendary Poets of Urdu Shayari

The magnificent palace of Urdu shayari was built by countless poets, but a few legendary architects stand out, whose work defines entire eras and styles. No discussion can begin without Mirza Ghalib (1797-1869), the undisputed master whose shadow looms large over all of Urdu shayari. Ghalib’s poetry is a complex tapestry of love, grief, philosophy, and wit. He confronted life’s paradoxes with a sharp intellect and a weary heart, creating couplets that are endlessly quotable and interpretable. His famous sher, “Hazaaron khwahishen aisi ke har khwahish pe dam nikle,” speaks of a thousand desires, each worth dying for, capturing the essence of endless yearning that defines the human spirit. Ghalib’s contribution elevated Urdu shayari to new intellectual heights.

The era before Ghalib was dominated by Mir Taqi Mir (1723-1810), who perfected the language of love and pain. His Urdu shayari is known for its startling simplicity and profound emotional depth. He wrote of heartbreak with a raw vulnerability that remains unmatched. If Mir is the god of love’s sorrow, then Allama Muhammad Iqbal (1877-1938) is the poet of the soul and the self. His Urdu shayari is a powerful call to action, urging the individual (khudi) to rise to their highest potential. In poems like “Lab Pe Aati Hai Dua Ban Ke Tamanna Meri,” he inspires hope, while in “Sitaron Se Aage Jahan Aur Bhi Hain,” he pushes the boundaries of human aspiration. His work is a philosophical cornerstone of modern Urdu shayari.

The post-colonial period saw the rise of Faiz Ahmed Faiz (1911-1984), who masterfully blended the romantic imagery of the Ghazal with the fiery passion of socialist ideals. His Urdu shayari is a beautiful protest, finding love not only in the beloved’s eyes but also in the struggle for a just world. Lines like “Bol ke lab aazaad hain tere” (Speak, for your lips are free) became anthems of resistance. Alongside him, poets like Ahmed Faraz and Parveen Shakir brought Urdu shayari into the contemporary age. Faraz continued the tradition of romantic and protest poetry, while Shakir, one of the most prominent female voices, wrote with startling freshness about a woman’s experiences, desires, and urban life, adding a crucial new perspective to the canon of Urdu shayari.

The Heart’s Vocabulary: Key Themes and Motifs in Urdu Shayari

The enduring power of Urdu shayari lies in its exploration of universal themes that resonate across time and culture. The most dominant theme is, without a doubt, Ishq—Love. But Urdu shayari distinguishes between different kinds of love: Ishq-e-Majazi (worldly or earthly love for a beloved) and Ishq-e-Haqiqi (divine love for God). Often, the former is used as a metaphor for the latter, especially in Sufi-inspired Urdu shayari. This love is rarely happy; it is defined by longing (justaju), separation (hijr), and the pain of unrequited desire (dard). The lover (aashiq) is a melancholic figure, forever devoted despite his suffering, and this very suffering becomes a badge of honor, a proof of the authenticity of his emotion.

Closely tied to love is the theme of Wafa (faithfulness) and Bewafai (unfaithfulness). The dynamics between the loyal, suffering lover and the cruel, indifferent beloved (maashooq) are a central drama in countless ghazals. Another profound theme is Fanaa—impermanence and the mortality of all things. The transitory nature of life, the world (duniya), and its pleasures is a recurring motif, urging the reader to look beyond the material towards the eternal. This leads to philosophical questioning (sawal) about the meaning of existence, the nature of God, and the human place in the universe, a theme Ghalib explored with unparalleled genius.

In modern Urdu shayari, these classical themes have been expanded to include strong currents of Jamaal (beauty) and a protest against Zulm (oppression). Poets like Faiz found beauty in the struggle for a better world, while the horrors of partition and political tyranny brought themes of grief (gham), rebellion (inqilaab), and human resilience (sabr) to the forefront. The beauty of nature, the hustle of city life, and personal introspection also became fertile ground for contemporary Urdu shayari, proving its ability to adapt and remain relevant to every generation’s hopes and fears.

More Than Words: The Cultural Impact and Recitation of Urdu Shayari

Urdu shayari is not confined to the pages of books; it is a performing art, a social activity, and a vital part of South Asian culture. Its most traditional platform is the mushaira, a poetic symposium where poets gather to recite their work before an audience. A mushaira is a vibrant, interactive event where the audience participates with cheers (waah-waah), snaps, and requests, creating an electric atmosphere. The etiquette of recitation, or tarannum, is an art in itself. A poet’s delivery—their voice, rhythm, and pauses—can elevate the meaning of the words, adding layers of emotion and emphasis. The late poet Jaun Elia was renowned for his unique, almost conversational yet deeply impactful style of recitation.

The reach of Urdu shayari was massively amplified by its marriage to music in the world of Indian cinema. For decades, Bollywood films have used Urdu shayari in their dialogues and, most importantly, in their songs. Legendary lyricists like Sahir Ludhianvi, Kaifi Azmi, Majrooh Sultanpuri, and Javed Akhtar were all accomplished poets who brought the depth and elegance of Urdu shayari to the masses. Songs like “Chalo ek baar phir se ajnabi ban jaye hum dono” (Sahir) or “Woh kahaan se humein tum mil gaye” (Javed Akhtar) are essentially ghazals set to music, making the art form accessible to millions who may not have read poetry otherwise. This fusion created some of the most timeless and beloved music in the world.

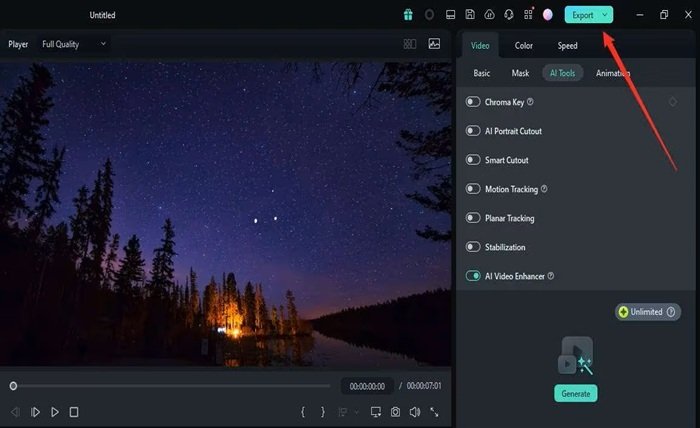

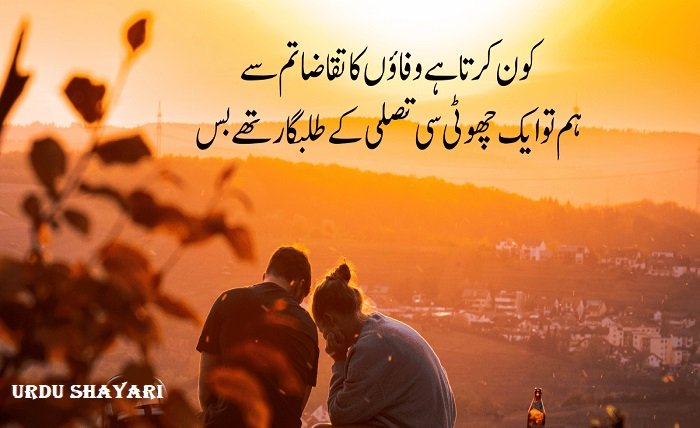

In the digital age, Urdu shayari has found a new lease on life. Social media platforms like Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube are filled with pages dedicated to sharing couplets, often superimposed on beautiful imagery or shared as short, recitation videos. This has democratized the art form, allowing new poets to share their work with a global audience and introducing Urdu shayari to a younger, tech-savvy generation. Online communities discuss and dissect the meanings of complex shers, proving that the ancient allure of Urdu shayari is perfectly adaptable to the modern world, continuing its legacy as a living, evolving conversation.

A Beginner’s Guide to Appreciating and Writing Urdu Shayari

For a newcomer, the world of Urdu shayari can seem daunting with its complex metaphors and cultural nuances. However, appreciating it is a journey of discovery that anyone can embark upon. Start by listening before reading. Seek out recordings of great poets reciting their own work. The emotion in their voice is a direct guide to the poem’s soul. Pay attention to the sound, even if you don’t understand every word; the musicality of Urdu shayari is a key part of its beauty. When you read, begin with translations and explanations. Many websites and books provide line-by-line translations and interpretations of famous shers. This helps build your vocabulary of common motifs like the moth and flame (parwana and shama), the spring (bahaar), and the nightingale (bulbul).

Don’t try to understand a full ghazal at once. Focus on one sher at a time. Sit with it. Read it aloud. Think about the two lines and how the second line completes, contrasts, or elevates the first. Ask yourself what the deeper meaning could be—is it about a person, a political situation, or God? Understanding the context of the poet (their life, the era they wrote in) can also add immense depth to your appreciation. For instance, reading Faiz’s work while knowing he was often imprisoned for his beliefs makes his metaphors of chains and dawn incredibly powerful.

For those inspired to try their hand at writing Urdu shayari, the first step is immersion. Read and listen to as much poetry as you can. Develop a rich vocabulary. Start by writing a two-line sher in English or your native language, focusing on creating that moment of impact in the second line. While meter and rhyme in Urdu are complex, you can begin by capturing the essence of the thought. The core of Urdu shayari is the expression of a genuine emotion or a unique observation about life in a concise and beautiful way. Whether you are a reader or an aspiring poet, the door to this world is open. All it requires is a attentive ear and a heart ready to feel. The journey into Urdu shayari is a lifelong pursuit of beauty and truth.

Conclusion

Urdu shayari is far more than an ancient literary tradition; it is a living, breathing dialogue with the human soul. From the royal courts of the Mughals to the digital screens of the 21st century, it has demonstrated a remarkable ability to adapt, survive, and thrive. Its power lies in its unique combination of linguistic beauty, structural discipline, and emotional honesty. It gives voice to the unspoken depths of our hearts—our most intense loves, our most profound griefs, our quietest rebellions, and our highest hopes. A single couplet of Urdu shayari can offer comfort in moments of despair, company in times of loneliness, and courage in the face of adversity. It is a testament to the power of words to capture the ineffable, to find beauty in brokenness, and to connect us across time and space through shared feeling. As long as humans experience love, loss, and the desire to make meaning of their existence, the melody of Urdu shayari will continue to resonate, an eternal echo of the soul’s most profound experiences.

FAQs

1. I don’t speak Urdu. Can I still appreciate Urdu shayari?

Absolutely. While knowing Urdu enhances the experience, many resources offer excellent translations and detailed explanations of the metaphors and cultural context. Listening to recitations also conveys a great deal of the emotion and musicality inherent in Urdu shayari.

2. What is the difference between a Shayar and a Shaayar?

There is no difference; it is simply a variation in pronunciation. Both “Shayar” (more common in North India) and “Shaayar” (common in Pakistan) refer to a poet who composes Urdu shayari.

3. What is the most important element in a Ghazal?

The most defining element is the radif, the repeating rhyme word or phrase at the end of the second line of each couplet. The consistency of meter (beher) and the self-contained nature of each sher are also crucial to the structure of a Ghazal in Urdu shayari.

4. Who is considered the greatest Urdu poet of all time?

This is highly subjective and often sparks passionate debate. Mirza Ghalib is most frequently bestowed with this title for his unparalleled philosophical depth and wit. However, poets like Mir Taqi Mir, Allama Iqbal, and Faiz Ahmed Faiz are also strong contenders for their monumental contributions to Urdu shayari.